When scurrying to get dressed in the morning, most of us do not have to think twice about whether or not our shirt matches our pants. Red shirt, blue jeans. Check. Shoes, backpack, keys. Check.

When scurrying to get dressed in the morning, most of us do not have to think twice about whether or not our shirt matches our pants. Red shirt, blue jeans. Check. Shoes, backpack, keys. Check.

But what if this red shirt was actually green? Or what if your jeans and shirt just appeared to be the same color in different shades?

Color blindness is a color vision deficiency, characterized by a person’s inability to differentiate between various colors. One out of every twelve people in the world have some sort of vision-related color deficiency, meaning that about eight percent of men and 0.04 percent of women are affected by colorblindness.

Will Walsh, senior, and Michael Laverty, junior, are two Leesville students affected by colorblindness. Both boys discovered this trait at a young age.

“My grandfather was colorblind, and when I was little my parents noticed that I could not get my colors right. They showed me an online colorblind test, and I failed it,” said Walsh.

Laverty’s colorblindness was discovered during a routine vision test at the doctor.

“When I was little my eye sight starting getting bad, so I went to the eye doctor and did some tests,” said Laverty. “One of them was a colorblindness test, and it came out that I am slightly red-green colorblind. I ended up getting glasses and now have contacts, but there’s nothing I can do about the colorblindness.”

Both Walsh and Laverty have red-green colorblindness, the most common form of colorblindness. Among men in the United States who are colorblind, ninety-nine percent are red-green colorblind.

Even though Walsh was classified only as having red-green colorblindness, he often confuses other colors as well.

“I mix up blue and purple, pink and gray, and yellow and green,” said Walsh.

Walsh and Laverty agree that getting dressed or picking out their clothes is the most challenging aspect of being colorblind, closely followed by having to read color keys in textbooks or on maps.

“I’m terrible at matching clothes,” said Walsh. “When I wear a tie for game day, I have to ask my mom if my tie matches correctly.”

“Colored pencils are the worst. Sometimes when we have to color something in class and there is a box of like a hundred color pencils, I can’t tell the red from the green and the brown ones. It’s not a big deal; I’ll just usually have to ask someone,” said Laverty.

When asked what the worst part of being colorblind is, Laverty responded that people who are inconsiderate or don’t understand bother him the most.

“People will ask me over and over again, ‘What color does this look like to you?!’ It’s really just rude,” said Laverty.

“The worst thing is when you try to say something about the color of something, and you say the wrong color, then I just look like an idiot, and I don’t feel like explaining it to friends,” said Walsh. “There is really no good thing about it.”

While color vision cannot actually be improved, color “sensation” can be adjusted. Scientists recently developed “Color Corrective Lenses,” which are like tinted contact lenses. Colorblind individuals use a colored lens in their non dominant eye. Both eyes see different colors because the brain takes some information from each eye.

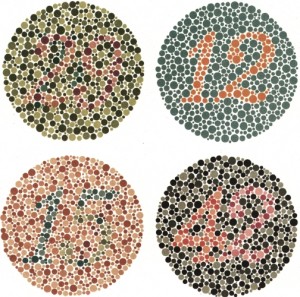

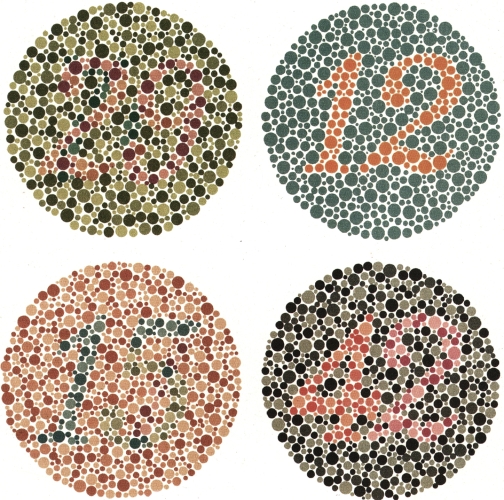

Manufacturers of the lenses claim that the wearers can pass Ishihara plates tests when using the lenses, but the ability to view other colors correctly may be lost.

Leave a Reply