As the Canadian national anthem plays at a March NHL game between the Winnipeg Jets and Pittsburgh Penguins, the Jets begin the game with three different nationalities represented in their six-man starting lineup.

From 1939 to 1945, the armies of Canada, Russia and the United States fought against the armies of Germany, Finland, Norway and the Czech Republic in the infamous conflict known as World War II.

Sixty-eight years later, all of those nationalities face off against each other on 30 diverse, culturally-mixed teams.

Not in trenches, but on ice. Not using guns and bullets, but rather sticks and a puck. Not on a bomb-scarred battlefield, but in the National Hockey League.

No well-known professional sports league represents as many foreign countries as the NHL. As of March 27, 18 different nationalities were represented among the league’s 30 clubs. Moreover, thirty individual nationalities had a player in the league at some time during history, ranging from Japan, Jamaica and Lebanon’s one to Canada’s 4,849.

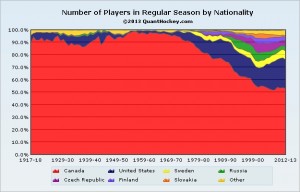

But Canada’s dominance in producing hockey stars is beginning to dwindle.

Cultural diversity has increased dramatically in hockey over the past 40 years. Increased interest in the United States as well of the emergence of hockey in Central Europe has allowed the percentage of non-Canadian players to increase tenfold over that time period.

The rapid expansion of franchises in the U.S., which currently contains 23 of the league’s 30 teams, has led to a record-high 23.2 percent of players in 2012-13 being of American descent. Sweden’s longtime affection for hockey is now rubbing off on its Finnish neighbors, a country which now boasts the sixth-highest total of current players. And hockey’s popularity is skyrocketing in central mainland Europe, too — combined, the Czech Republic (41 players), Slovakia (12), Switzerland (8) and Germany (8) would compose the third-highest total of players.

Even the league’s racial diversity is beginning to expand. Of the 72 black players who have ever appeared in the NHL, 28 of them — more than a third — are active today. That number could soon become 29, as Seth Jones, an 18-year-old defenseman, could, come June’s draft, become the first black player drafted first overall.

All of that international diversity does not come without conflict, though. The half-century-long tenseness between the U.S. and Russia are evidently visible, even today, in the hockey universe; both the NHL and the KHL, Russia’s own professional hockey league, frequently spar over player rights and contract legitimacy. Caught in the middle are such Russian NHL superstars as Lubomir Visnovsky, Alexander Ovechkin and Ilya Kovalchuk, who created headlines in January when contemplating whether to return to North America after the lockout.

Clusters of single-nationality players on certain teams often bring ethnic stereotypes to the forefront, as well.

Adam Oates, the Canadian head coach of the Russian player-laden Washington Capitals, has been criticized as being “too sophisticated and confusing” for such a team. The Detroit Red Wings are often known as a Swedish team; the Anaheim Ducks and Carolina Hurricanes are known as Finnish destinations.

The NHL has also had its own recent brushes with racism. In 2011, a banana was thrown at Wayne Simmonds, a black forward for the Philadelphia Flyers, during a preseason shootout attempt. Last year, Joel Ward, a black forward for the Washington Capitals, scored a playoff series-winning goal in Boston and subsequently received hoards of death threats and Twitter insults in the following hours.

As the game continues to evolve internationally in the coming decades, hockey should continue to play a starring role in the gradual global intertwining of sports and culture.

Leave a Reply