For over 150 years, students have been grouped by their academic ability in school. This grouping, called ability grouping or ability tracking, has been a continuous and controversial topic in America.

Grouping students by their academic ability began in the 1860s. The practice had a rise of popularity in the 20th Century as intelligence testing was introduced.

Ability grouping is a practice created to group children by their strengths and weaknesses in the classroom. There are two common ways that ability grouping is introduced into school. One way being, small groups with-in classrooms and and the other being classroom to classroom grouping (also known as ability tracking).

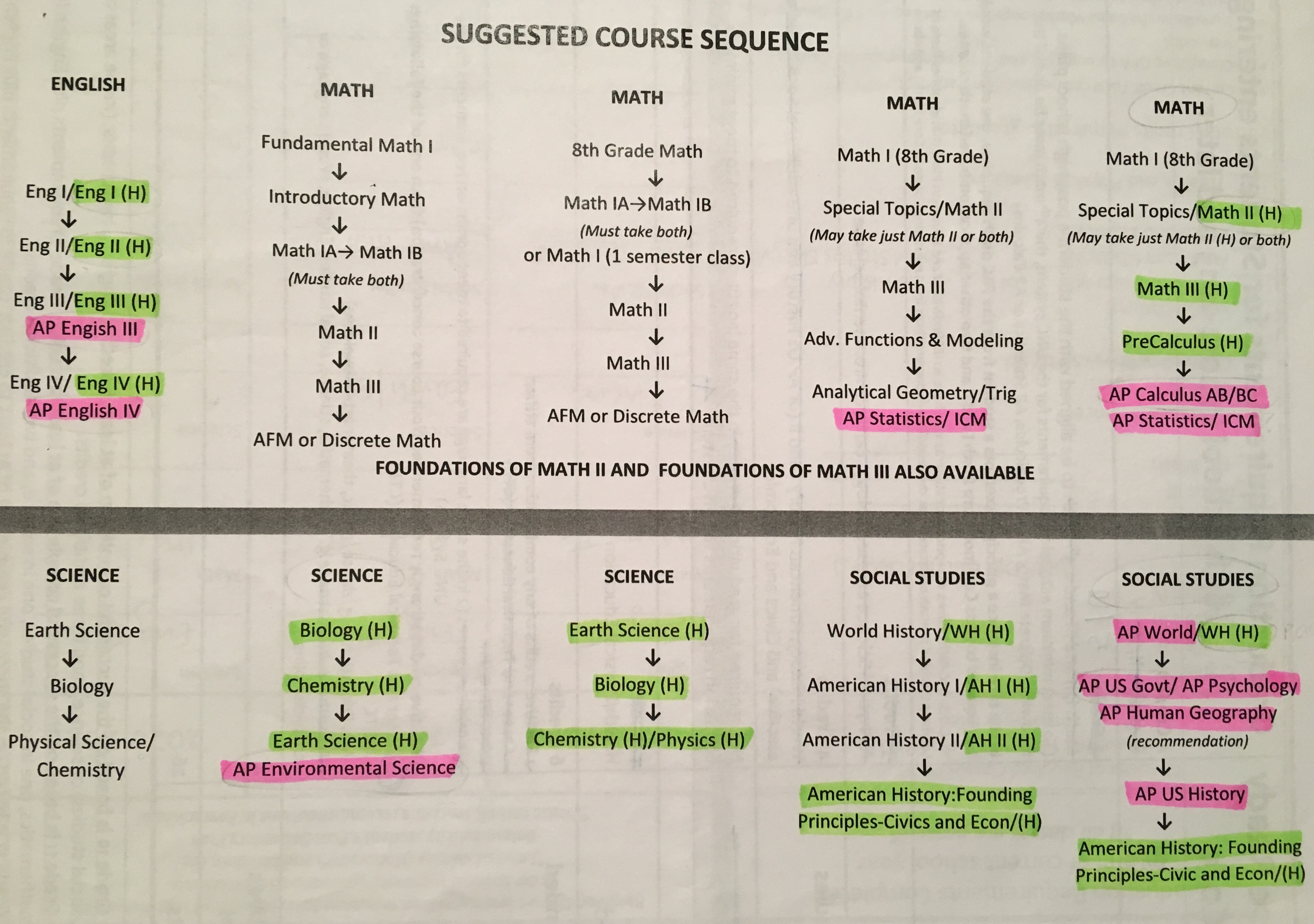

Ability tracking is intensely more obvious to a student than ability grouping, the separation of academic ability is what is more clear to students. Ability tracking includes, AP (advanced placement), Honors classes in high school, to AIG (academically or intellectually gifted) in elementary school.

The practice was introduced to allow teachers “to tailor the pace and content of instruction much better to students’ needs and, thus, improve student achievement,” according to an article by NEA (National Education Association).

Ability grouping is beneficial in other ways besides its original purpose, such as allowing students to benefit from interaction with academic peers of similar ability. Students who are in higher paced classes tend to need less attention from the teacher in hopes that they will begin to use higher level thinking. Students of a lower pace may receive a higher level of repetition and reinforcement from the teacher. In order to benefit their understanding of a topic, thus increasing their academic achievement.

However, the practice raises many concerns. Ability grouping has become controversial over the years: Students who are grouped in higher achieving classes get a better quality learning experience than students who are in classes of lower ability. The practice has also been depicted to channel poor and minority students into lower achieving classes, leading to the students receiving a lower quality education.

According to an article by EW (Education World), in an experiment developed by Robert E. Slavin in 1986, Slavin determined that some forms of grouping are more beneficial for student achievement than others. In some cases of ability grouping, students are grouped heterogeneously in classes for most of the day, for a specific subject. Slavin discovered that there was an increase of student achievement in the areas that they were separated for. The Joplin Plan (grouping of students by reading ability) effectively improved student reading achievement. Finally, Slavin came to the conclusion that in-class grouping did somewhat benefit student achievement–mostly in the area of math rather than reading because it’s especially hard to find small control groups for such a broad, comparative study that is literature.

Author of a book called Crossing the Tracks: How “Untracking” Can Save America’s Schools, published in 1992, Anne Wheelock contradicts Slavin’s studies and is one of many who believe that ability grouping should be banned. She believes that a student’s academic ability is too widespread and extensive to be deduced into groups.

So, should ability grouping be allowed in schools? There are clear pros and cons to the practice, but a balance of ability grouping and no separation in classrooms is the most effective way to increase student achievement. Students can be separated for a portion of the day for certain subjects such as math or reading, and then come together for the rest of the day, which was found to be effective in Slavin’s experiment. This is most effective for elementary/middle school students who have a smaller range of classes and a constant schedule.

High school students can have balanced ability grouping and tracking as well. A large majority of high schools offer AP, Honors, and Academic courses. Inside those classes, there tends to be a mixture of students with similar academic ability. Within the classes, teachers can effectively use ability tracking by creating temporary groups that can last an hour, a week, or even a month. The groups do not have to be permanent, but they are a way for students to work together in a variety of ways depending on activity and learning opportunities.

Are schools effectively applying ability grouping and tracking? Yes, some are, some encourage the idea too much, and others don’t find it effective at all. If all schools were to balance the practice, each student’s learning needs would be accommodated for, not one group of students more than the other, but all students equally.

Hi! My name is Asis, and I am the social media editor for The Mycenaean. I am a member of National French Honor Society, the French Club treasurer, a swimmer, and a camp counselor at Brier Creek Community Center. My favorite book is Wonder by R.J. Palacio. Also, I like J. Cole and H.E.R.

Leave a Reply