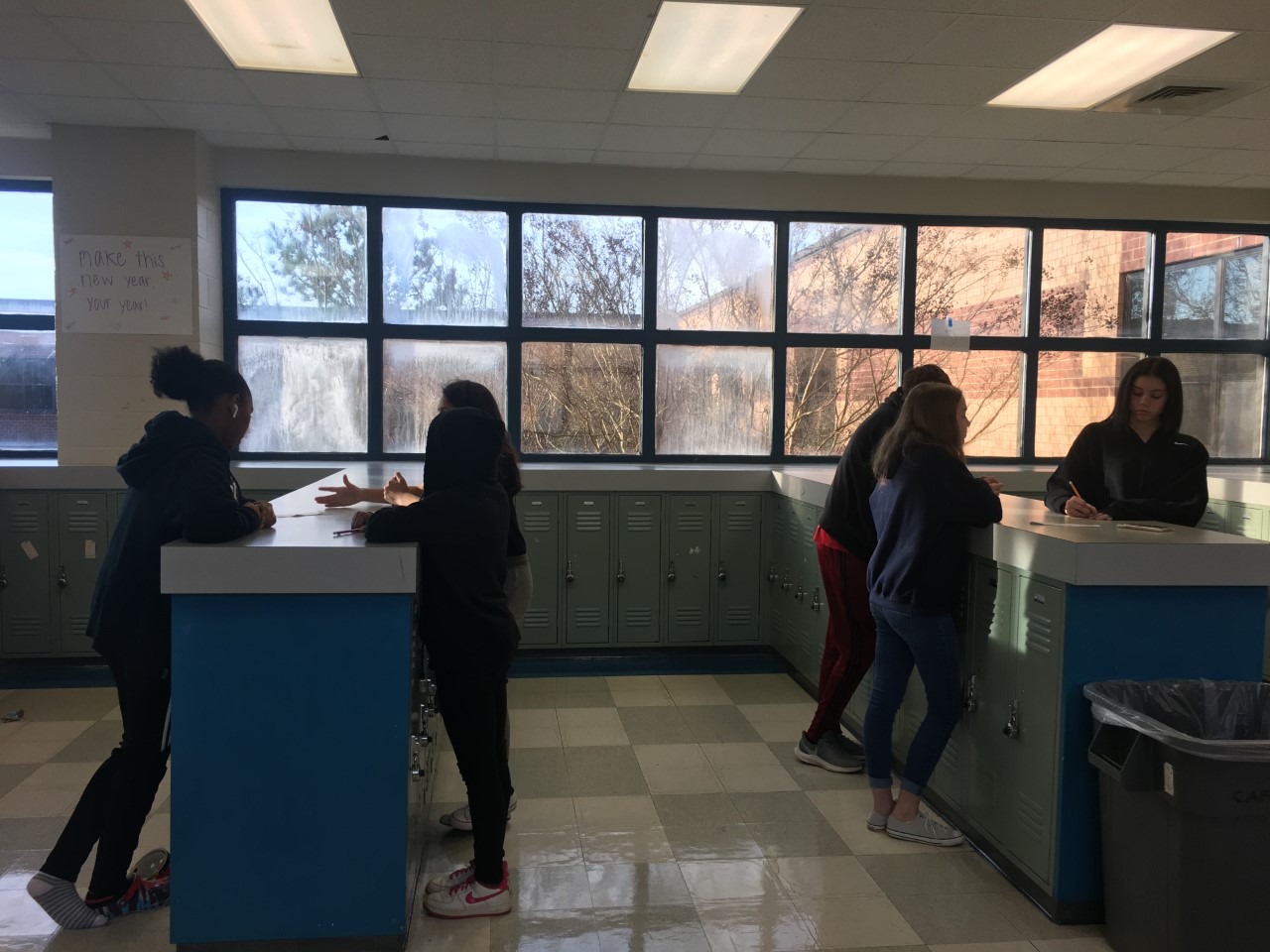

One English class at Leesville completes a group assignment in the locker bays. Group projects are common, with various responses from students. (Photo Courtesy of Ellie Thompson)

Most everyone has dreaded group projects — finding time to collaborate, taking on extra work, and having a massive piece due at a way too close deadline. Mostly, you’re on one of two sides: excited to push your work off on someone else or fearing how your classmates’ work will affect your grade. At times, group projects can cause your grade to plummet because of work that you weren’t designated to complete.

Here’s the hidden truth — this situation is against school policy. Teachers should not be able to limit your grade based on the performance of another student.

The Wake County Board is “committed to maintaining rigorous performance and achievement standards for all students and to providing a fair and consistent process for evaluating and reporting student progress that is understandable to students and their parents and relevant for instructional purposes.”

In addition, “grades should be given in reference to a student’s achievement of the learning objectives defined for the class, and should not be limited by the performance of other students in the class,” according to Wake County Policy.

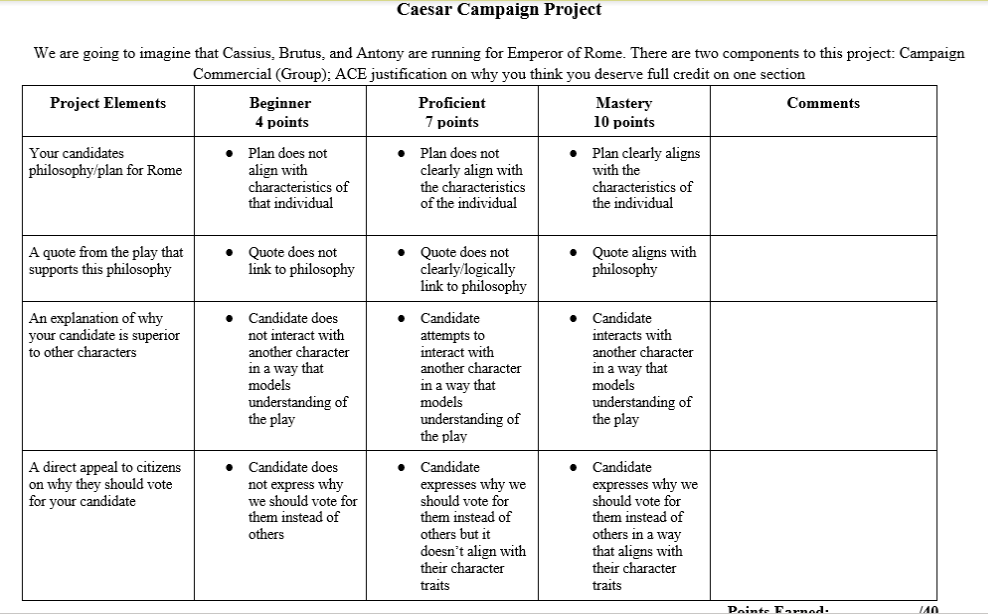

Teachers cannot base a student’s grade or their performance on the work of one of their peers. Every teacher should be able to explain to each student the specifics of what they need to work on. Teachers need to have a reason for the grades they give, and the students should know them. These specifications — such as creativity, grammar, or presentation — are often seen in rubrics — a clear layout of expectations individualized for each student. Teachers layout categories (see rubric insert) you must fulfill in order to meet to satisfy the objectives.

“We divided up the work, but it didn’t really get done, so I had to do it all the night before. It didn’t end up that good,” said Reagan Dunkley, senior, about a group project he participated in. Occurring too often, one student takes the brunt of the work, but all receive the same grade. His grade was limited by the lack of performance of his classmates, which is against policy.

Unfortunately, this situation is more common for students than it should be. The late-night scramble to cover your partner’s work can be frustrating, especially if your teacher doesn’t know how much work you completed.

If your teacher assigns a project for you to complete with two other students, if one of them completes their portion of the work late while yours is on time and you receive the same late grade, your teacher is allowing your grade to be “limited by the performance of other students in the class,” directly against school policy.

If a student completes no work while their group mates complete it for them, they have demonstrated no mastery of the concepts. If then they receive the same grade as their peers, it wouldn’t be earned, not meeting the qualification of “grades… given in reference to a student’s achievement of the learning objectives defined for the class,” again against policies.

If a teacher gives a grade based on work ethic, whereas part of a group project, a student doesn’t work hard, there is no way to measure the knowledge of that student, and any grade given would be incomplete. Teachers should give grades based on “achievement of the learning objectives” fixed beforehand, as in a rubric, and the teacher would have no way to measure that.

Francis Flemming, a sophomore, talked about a group project he participated in in a Spanish class. His portion of the project was complete — he finished the slides and fulfilled the requirement of knowing the material well enough not to read directly from them. His partner, however, didn’t. Instead of an A, which he could have received, their project finished with a B, but his work wasn’t the limiting factor. His partner not reaching the objectives dropped his grade in clear violation of policies.

What are teachers doing to protect this policy, to ensure it is upheld?

“Grading policies and practices abide by board policy at LRHS but also are consistently reflected on by individual teachers and collaboratively, in the PLT (professional learning team) time,” said Maria Mills, assistant principal via email.

“Ultimately, it is the individual student that needs to be successful in learning the standards,” said Mills. Consistent with the standards, Mills states that students should earn a grade for their work and not be “limited by the performance of another.”

“The balance between group work and independent work is validated through the use of independent rubrics and expectations throughout the semester; not on one particular assignment,” said Mills.

But, if a class is largely based on projects and group learning, and if multiple major assignments negatively impact your grade, that is against WCPSS policy. Yes, there is a balance, but if any assignment (group or individual) doesn’t show that you have mastered the objectives, it stands directly against policies. The balance of a student’s grade reflecting their learning and teachers maintaining a standard that shows it often gets lost.

It is a difficult balance — where does one student’s grade end and the next begin in a collaborative project?

There is often confusion in this for teachers, but they should be fully aware of these policies and be taking active measures to uphold them. But what power is given to students if they feel these standards aren’t supported by their teacher?

In the end, individual mastery and achievement should define each grade. Overall, your grade, if “limited by the performance of other students in the class” will not accurately reflect what you have achieved separately from your group mates.

This is what administrators and teachers might claim is set in place at Leesville. Most often, students are able to see it in their classes. Is it what you’ve seen?

Hi! My name is Ellie and I am the editor in chief for The Mycenaean. I play soccer at NCFC and go to The Summit Church!

Leave a Reply