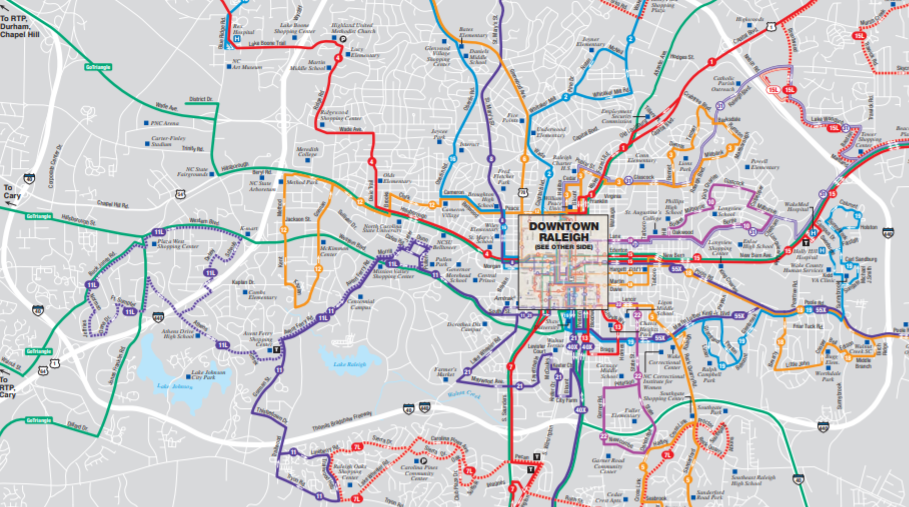

GoRaleigh, the transit system responsible for operating most of the public transportation services in Raleigh, operates 27 fixed routes. The system focuses on downtown, and branches out from the city’s municipal area. (Photo courtesy of Marie Cox)

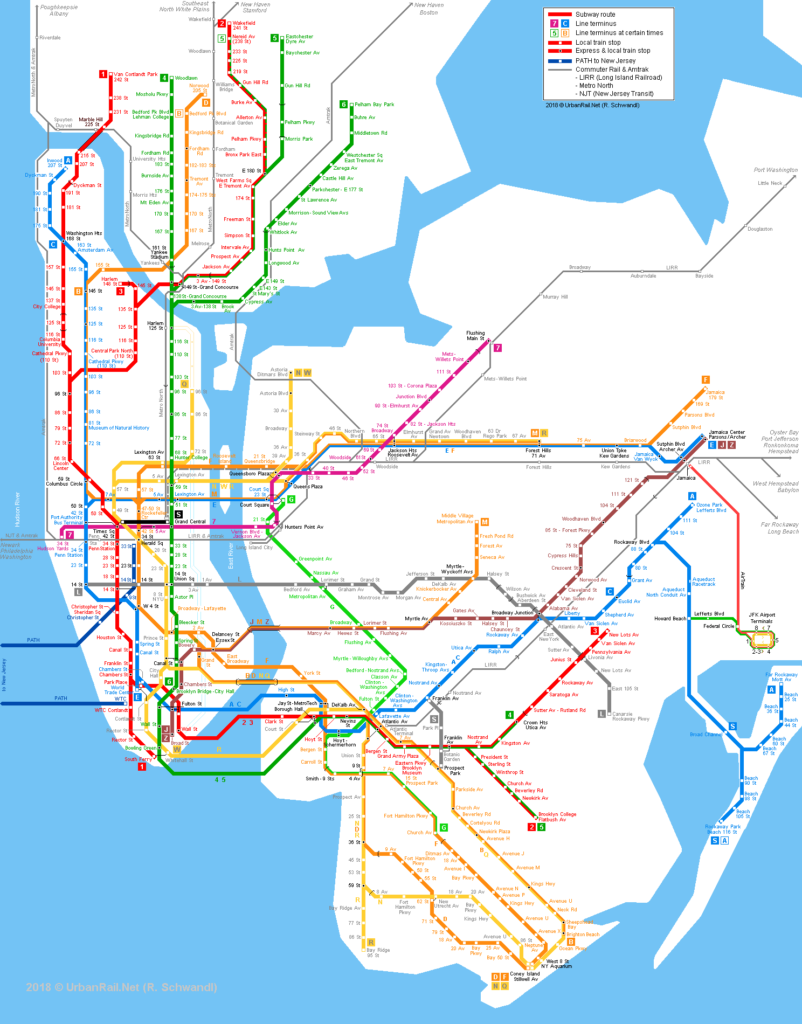

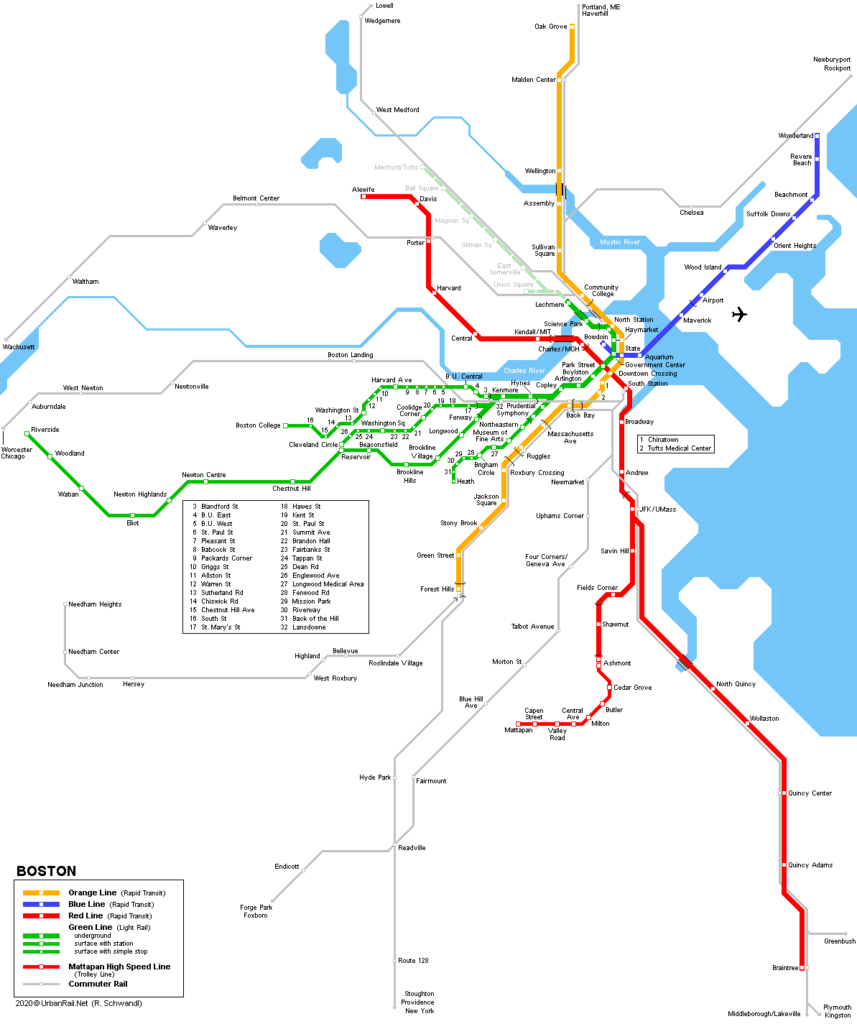

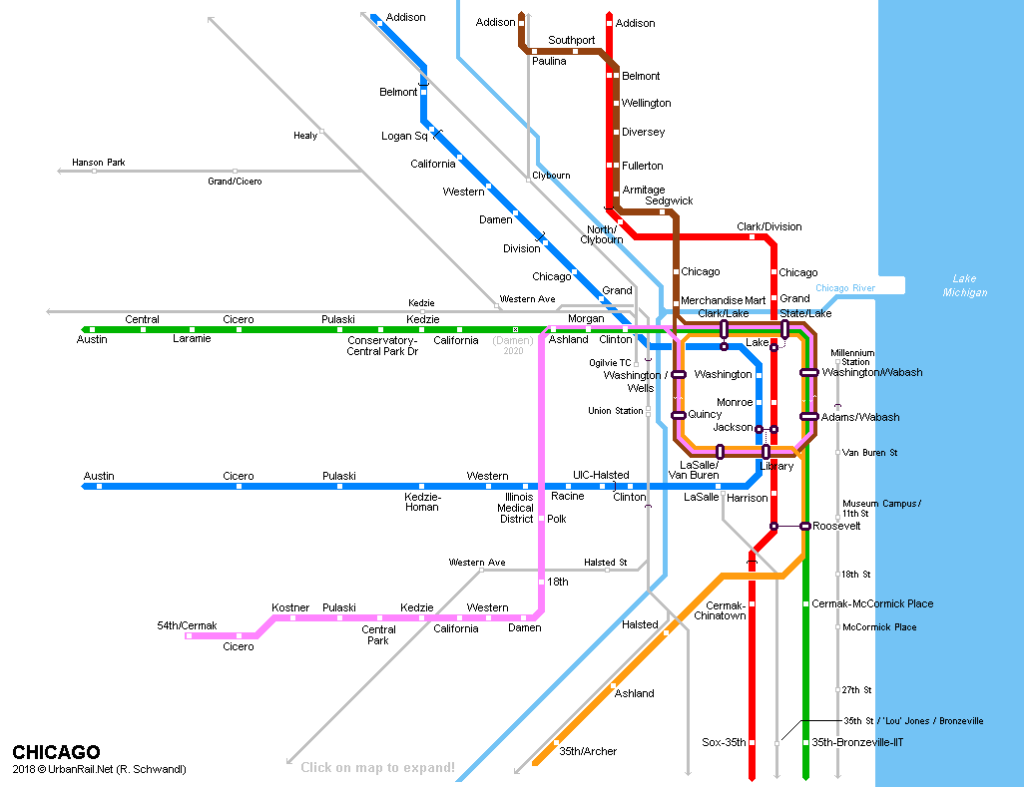

If you look at the design of major cities’ train systems, it’s not hard to figure out what they were built to do. In New York City, Boston, and Chicago, all the different transit lines intersect in downtown and then fan outward to the suburbs.

New York ((Photo in the public domain)

Boston ((Photo in the public domain)

Chicago ((Photo in the public domain)

Public transportation systems that intersect downtown are good at moving people between the suburbs, the outer rings of the city, and downtown.

Transit systems across the US serve a very specific type of commute: one from outside the center of the city to inside it, and back out again. However, studies show that today the most common American commute is actually from suburb to suburb — a route that US public transit doesn’t serve.

Even cities like Raleigh can see the majority of jobs being suburb-based, not downtown. Over 48,000 people work in downtown Raleigh. But Research Triangle Park (RTP), located outside of downtown, has 50,000 workers alone.

Raleigh’s public transit system also falls in line with other American cities. All of Go Raleigh’s routes meet downtown and don’t heavily service suburbian areas.

The commute from suburb to suburb is one reason that the overwhelming majority of Americans get to work by driving alone.

Driving isn’t always ideal, though. First, it requires many Americans to own a car in order to work. Car ownership is expensive: it’s the second-biggest household expense for Americans. All that driving also means that transportation is the single biggest way Americans emit greenhouse gases.

Most Americans don’t rely on public transit, rarely making it a top political priority, which makes things even harder for the people who do rely on neglected transit systems.

What would it take to get more Americans to use public transit? Who has the power to make that happen?

How We Got Here

Let’s look at Cincinnati in 1955 compared to 2013.

In 1955, it’s what a lot of American cities used to look like. There were some highways, but most of the city was on a grid. The grid system made it easy to get around either on foot or on public transit.

Come 1956, a huge government infrastructure project changed the US dramatically. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 meant the construction of new interstate highways from coast to coast, many of them running right through the downtowns of cities.

Now, Cincinnati has a tangle of highways enclosing their grid system. The highways make some neighborhoods almost impossible to get to on foot. If you don’t drive, it’s hard to get around the city at all due to the major roadways.

The same thing happened in countless other cities, like Detroit and Kansas City.

[slideshow_deploy id=’24750′]

As cities expanded outward along highways, one kind of neighborhood flourished: residential, filled with single-family homes. These new neighborhoods sprawled out, which changed how Americans got around. Living in a purely residential area required you to travel a lot farther for just about anything.

A study found that the average workday distance traveled for Americans was 7 miles. 7 miles in a car doesn’t sound long at all. Driving, 7 miles is only about 10 minutes.

Traveling that distance to work without a car is a little less simple. It’s a biking distance that is both strenuous and potentially unsafe, and for pedestrians, it’s a walk you can’t complete in any kind of reasonable time.

Beyond traveling to work, the development of major roadways meant that teens who don’t drive became dependent on people who do.

This type of travel distance and lack of walkability highlights the consequences of what we’ve built. Our highways and suburbs created automobile-oriented neighborhoods.

In the early 1990s, a new approach to neighborhood planning created places that look more like Oakland, California. Neighborhoods designed to put you closer to what you need. They’re centered around a transit hub, with buildings that contain not just housing, but office space and businesses, too.

These neighborhoods are an example of what people call transit-oriented development. The people who live in these places are less likely than the national average to drive, and more likely to walk, bike, or take transit. However, developing new neighborhoods like this is a long-term project.

Solving Public Transit

If we’re going to address the issue of public transit, we have to accept the world that we live in now. The US can’t redesign all existing suburbs to match transit-oriented developments.

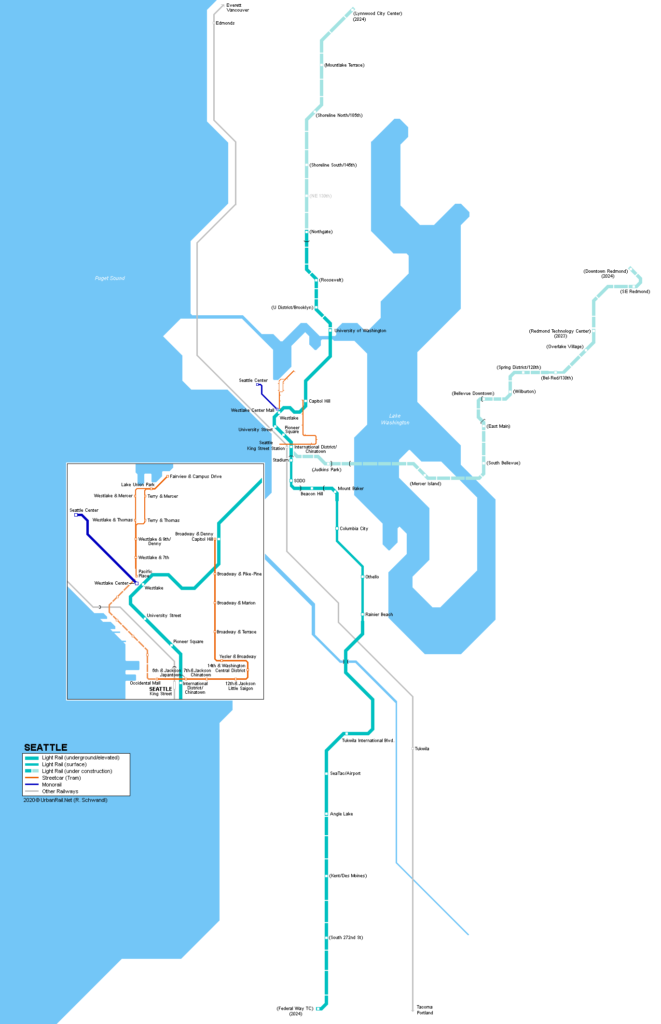

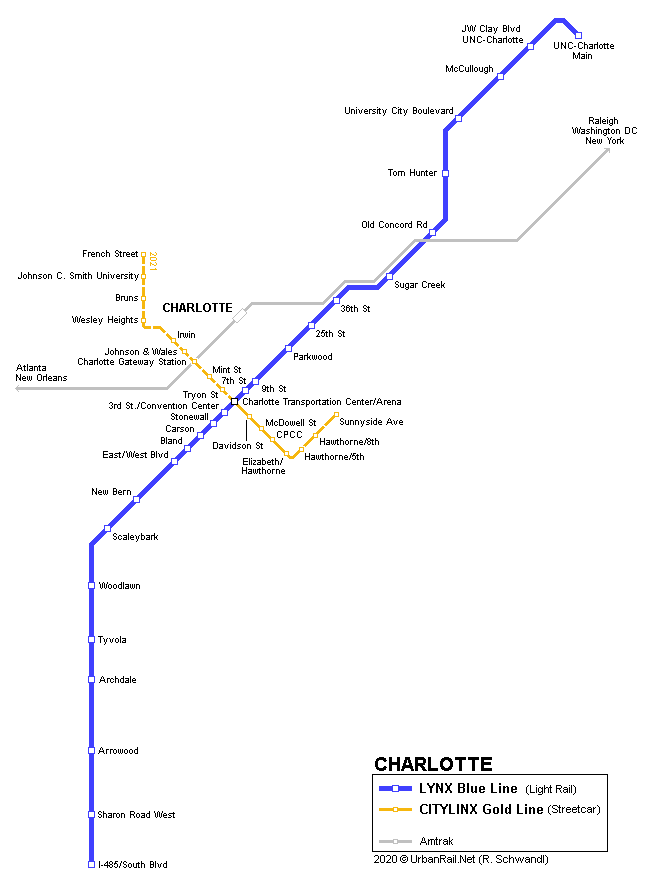

Most American cities have public transportation that offers service that’s oriented around downtown and not neighborhood to neighborhood. You can see that from big cities like Seattle to smaller ones like Charlotte.

But in other cities across the world, like Toronto, that’s not the case.

When you go to a Toronto suburb, it’s almost identical to an American one. You see houses with big driveways, two-car garages, and winding suburban streets. The difference is that the bus goes past those single-family homes every five minutes, and it runs 24 hours a day.

That difference changes everything.

Even car owners in Toronto ride the bus. That shows that it is possible to have reliant public transport that meets the needs of Americans. The fact that even car owners ride the bus proves that if America invests in basic operations and improving basic local service, riders will come.

Funding for public transit

State and local governments provide over half of the funding that goes towards public transit. That makes state and local elections incredibly important to public transit.

Right now, the federal government contributes the smallest part to public transit funding– about 17%.

Very little federal transit funding helps pay for day-to-day operations, even though that’s often where transit systems need the most help.

Instead, most federal money gets directed to “capital investments”: flashy new physical infrastructure projects that often garner media attention.

The federal government supports less than 10% of operating expenditures, but almost 40% of capital expenditures.

So cities end up with a billion-dollar rapid transit project, or light rail, or bus rapid transit project, where the vehicles don’t actually run that frequently.

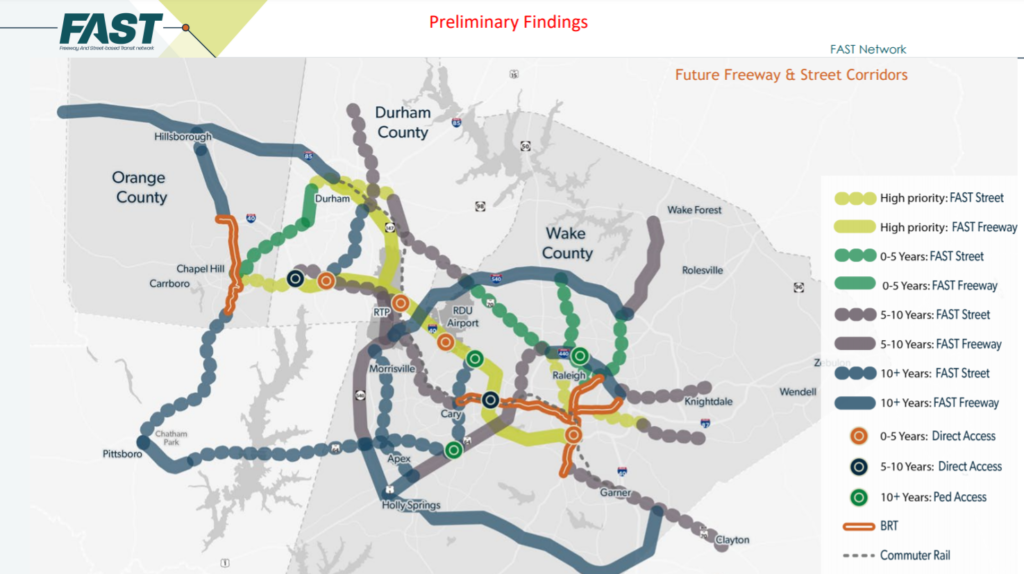

In Raleigh, we’ve had a failed light rail project and are now moving onto a regional Freeway And Street-based Transit (“FAST”) network project. The FAST network concept seeks to transform roadways into multimodal freeways and streets. The proposed network incorporates multiple connections between cities and towns, Research Triangle Park, and RDU Airport.

The network is far from being ready to implement, but it outlines immediate low-cost transit options for high-impacted freeways and streets like Six Forks Road and Capital Boulevard.

While the project, in theory, is more connective than what we have now, it doesn’t solve the issue of public transportation not being accessible to neighborhoods.

Biden’s plan for transportation

President Joe Biden touches on plans for public transit on his campaign website, mentioning goals for investment in public transportation:

Provide every American city with 100,000 or more residents with high-quality, zero-emissions public transportation options through flexible federal investments with strong labor protections that create good, union jobs and meet the needs of these cities – ranging from light rail networks to improving existing transit and bus lines to installing infrastructure for pedestrians and bicyclists.

While his words sound nice, the President hasn’t released plans for public transportation. Ultimately, where the money for public transit goes is really decided by Congress.

In Congress, debates over funding public transit split along partisan lines. Democrats, who often represent more urban districts, end up in favor of more transit funding; Republicans tend to be in favor of more funding for highways and roads.

In July 2020, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives passed a 1.5 trillion-dollar infrastructure bill, re-allocating funds from roads to trains and transit.

The bill had no future in the Senate — at least not in July when it was still Republican-controlled. Now, the Senate has a 50-50 Democratic-Republican tie, which means Vice President Harris has the tie-breaking vote.

With the U.S. House continuing under the leadership of Nancy Pelosi, both chambers of Congress are Democrat-controlled.

Since that’s the case, we can actually expect to see significantly more interest in investment in public transportation, and interestingly, a different approach to that investment. It may not just be more capital projects, but different kinds of investment in things like operations.

The bottom line

Most Americans live in places designed for cars. If we want to change that in the long term, we’ll have to build communities that look different and are transit-oriented.

Right now, Americans drive because it’s the most convenient option.

That’s a good thing: that means that you don’t need to transform a whole country to get more people to ride public transit. You just need to make it convenient enough that they want to.

Hi! My name is Marie, and I am the editor-in-chief of The Mycenaean. I am also President of Model UN and President of Quill and Scroll Honor Society. I love whitewater kayaking and rollercoasters.

Leave a Reply