Francis Bellamy’s Pledge of Allegiance is a symbolic part of the United States’ patriotism and history. The pledge, originally introduced in a magazine called The Youth’s Companion in 1892, has faced a couple of changes within the past 100 years. The most recent pledge is as so:

“I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic, for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

However, with the changes that have resulted in this version, a lot of controversy has erupted over the structure of a pledge taken by students across the nation. Obvious questions of the religion and the honesty of the statement have resulted in masses of students refusing to say the pledge.

The biggest controversy is saying that we are one nation under God. “Under God” was added to the pledge in 1952 under the Eisenhower administration. Experts claim that the addition of “under God” was meant to add a sense of faith to the pledge during a time when the nation was facing the threat of communism, but the pledge then contradicts itself by claiming liberty for all, while imposing religion upon the public.

The constitutionality of the line has been brought before the court on several occasions, some state courts such as one in Scramento, California, ruled the recital of the pledge in public school unconstitutional due to the “Under God” clause. Whereas other states, such as Virginia, upheld the constitutionality of the pledge in schools.

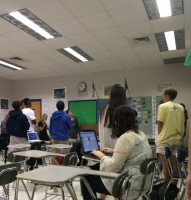

Aside from the literal pledge, the effect that the ritual has on the public draws parallels to a dystopia. Every morning students solemnly and seriously repeat the pledge, some with their hand over their heart, in unison with each other. It’s almost a habitual occurrence, and the pressure to conform and say the pledge puts students in uncomfortable situations.

When I moved back to the U.S. in 2007, I went to public school and had my first experience with the pledge. I didn’t understand the meaning of the pledge, but I don’t remember ever hearing an announcement that it was optional so I felt compelled to follow everyone else and learn the pledge.

For a brief period in middle school, they began mentioning it being optional, and I stopped saying the pledge mostly because I was a Canadian, and I felt that I did not have the ties to this country the way citizens do. When I acquired my citizenship in the 10th grade, and I had to say the pledge with all other new citizens in the ceremonial room of the Durham Homeland Security office, I felt the patriotism of the room. And I began to say the pledge again.

Yet, saying it every day, I naturally began to look into the meaning of the pledge. And I noticed the solemn effect it had on the other students, and so, for a different reason, I stopped saying the pledge again. Even so, my vacillating opinion legitimizes the controversy over whether or not the pledge is appropriate.

To be clear, I understand the patriotism that the pledge represents and how it promises to establish a nation that is indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. These are all valid and necessary pursuits — however, the pledge creates an illusion of what we are not. There is undeniably still racism, sexism, and general inequality in this country. A nation can never be completely rid of these issues, but there is still a lot of work that should be done to minimize these inequalities.

The way the pledge is stated puts the responsibility of these ideals upon the republic and not the people. The structure of the pledge disillusions the public into thinking they have no part in fixing the problem, or worse, that the problem does not exist.

The United States is looked upon as a land of opportunity, and the potential for the country’s continual improvement is great. The pledge sets a goal that the nation should continue to strive for, but saying the pledge ritually every day, in a stressful environment such as public school, pressures students into ignoring the true integrity and importance of the statement.

Leave a Reply