For Americans, it is entirely legal to take a drug for, say, ADHD as long as it has been prescribed by a certified doctor. It is also acceptable (with a prescription) to enhance mobility and strength with steroids. There have also been enhancements to cognitive functioning with so called “smart” drugs (see The Perfection of Us).

But why stop there? If prescription drugs enhance these certain aspects of life, why not extend greater enhancements to create an even better human? Seemingly radical genetic fixes in vitro could improve and save the lives of millions. Imagine a baby in the womb diagnosed with Down Syndrome, and all it would have taken to fix was the simple extraction of a chromosome before the embryo is implanted into the mother’s womb.

Or perhaps it is a military veteran who, back from war time, is damaged both physically and mentally; he has lost two limbs along with all the personality that makes him unique. A simple alteration to his damaged brain paired with a surgery attaching enhanced prosthetic limbs, and just like that–he is nearly the same man he was.

But where do we draw the line at what’s unacceptable? What makes it OKAY to alter a baby’s genes, or change a man’s brain chemistry, but not acceptable to do the same thing to other people? But instead of a baby with Down Syndrome, it’s a healthy infant whose parents merely want to make their child stronger, faster, taller, better than their original genes coded for. And instead of a military veteran, it’s an elderly man afraid to die and only wants one simple surgery–just one–to make him feel young and healthy and alive again.

When do we cross the line?

Scientists are one step away from genetically modifying human offspring. As stated earlier, if we could change the gene for Down Syndrome or perhaps a gene coded for cancer, why not change…everything else? The only thing between being ordinary and supreme would be a conversation with a geneticist and a quick switch of a coded gene.

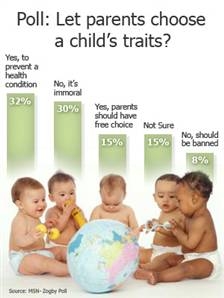

An article in LiveScience referenced the fact that humans today already genetically modify various crops and animals. There is a very thin line prohibiting parents from creating their “designer babies”, for it is legal in the United States, but it is heavily regulated.

Heather Long, in The Guardian, described a time where a troubled couple did not have the capability to produce children on their own. They underwent the IVF process which allows the parents to create an embryo in a petri dish and then prepare it for implantation. The couple was able to look the genetic codes for each of their embryos. This allowed them to see which embryos would be most likely to attach, and therefore would be the most likely to survive.

But it won’t be long until parents move from just wanting a baby, to wanting a baby free of disease possibilities, to wanting a baby with certain traits, to wanting a baby they can design themselves. “From there, it’s not to hard to imagine something akin to the Subway sandwich line where you select different traits a la carte,” wrote Long.

Michelle Desantos, author of an article in SFCtoday, made an interesting point that society must also think in terms of the future. There is already so much expected of a natural born baby–to be brilliant, funny, beautiful, athletic–imagine what would be expected of a designer baby, the seemingly “perfect” child. If they were not to live up to their expectations, they would be ridiculed for not living up to their destined perfection.

An article in How Stuff Works mentioned that some diseases are more common in one gender than the other. For example, hemophilia–a blood condition where the blood doesn’t clot correctly in response to a cut or injury–is more common in males than in females. A family planning for IVF may choose to have a female embryo implanted if they have a family history of hemophiliacs. “Some people worry that it could lead to an imbalance between genders in the general population, especially in societies that favor boys over girls, such as China,” wrote Kevin Bonsor and Julia Layton.

Even if the parents weren’t interested in creating a designer baby, and only wanted to rid their child of disease ridden genes, there are still issues that arise. A disease-free child will have a predicted life span of 100-150 years. Desantos wrote, “And as if our world isn’t overpopulated enough, a longer life span can also put a lot of strain on the supply of natural resources, along with limited living space.”

But there are also positive effects to consider. While yes, much of society is appalled at the thought of these “designer babies”, there are many other factors to take into account. As stated before, the new age of science allows experimenters to discover ways to prevent diseases such as cancer or hemophilia before the child is even born.

Why would parents, when given the choice, choose to not rid their offspring of these harmful genes? The child could live carefree and not have to worry about if or when the cancer will reveal itself. And if the child was destined for Down Syndrome, that simple extraction of that one–one–extra chromosome would be the difference between a normal and near-perfect life. Shouldn’t a parent want that for their child?

And so, the question is, when do we cross the line?

Leave a Reply